Being an Historical Account of the Life, Travels,

Sufferings, and Christian Experiences of that

Ancient, Eminent, and Faithful Servant of Christ

GEORGE FOX

1624 – 1691

Modernized into Contemporary English

with Timeline & Travel Maps

This edition prepared 2026

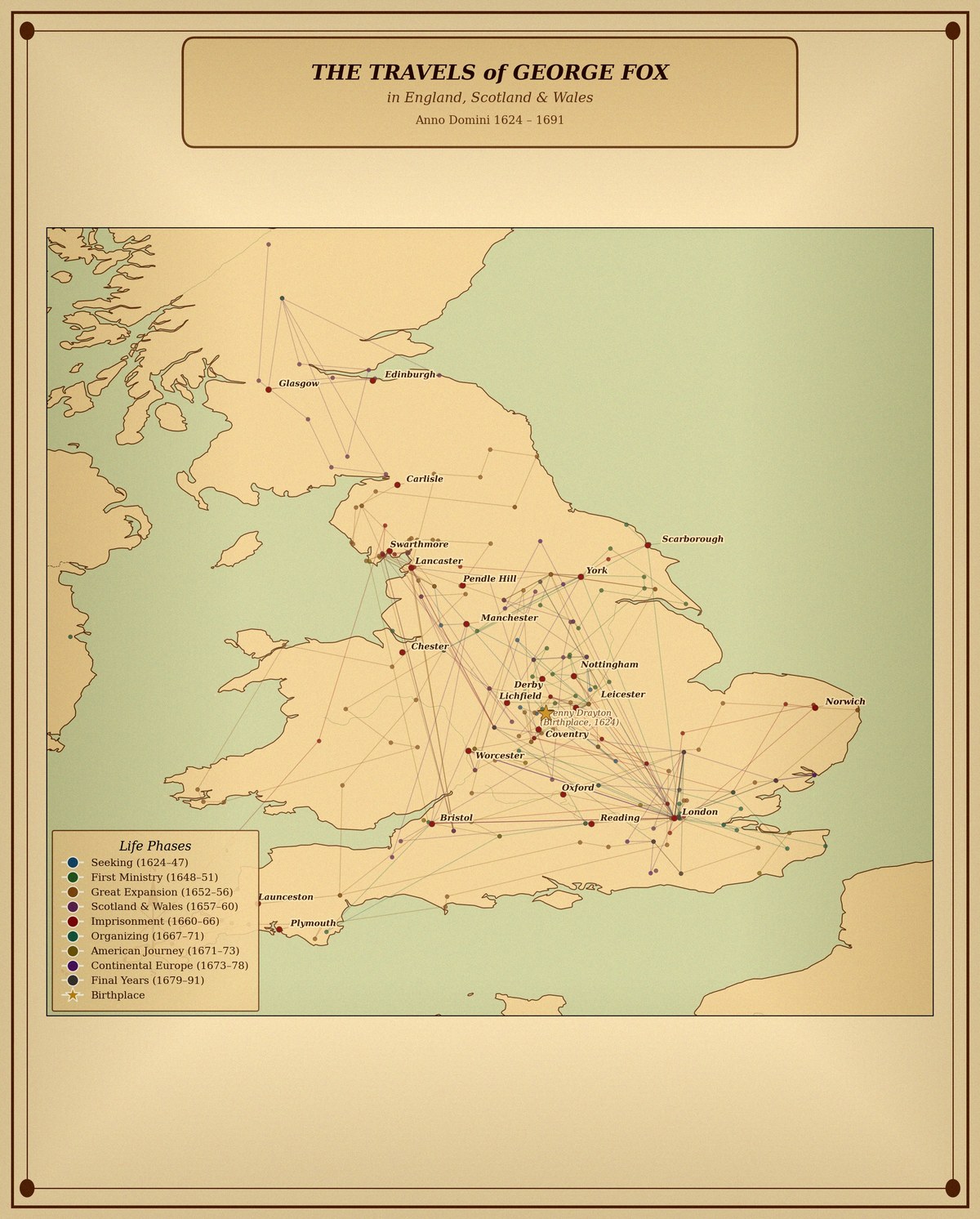

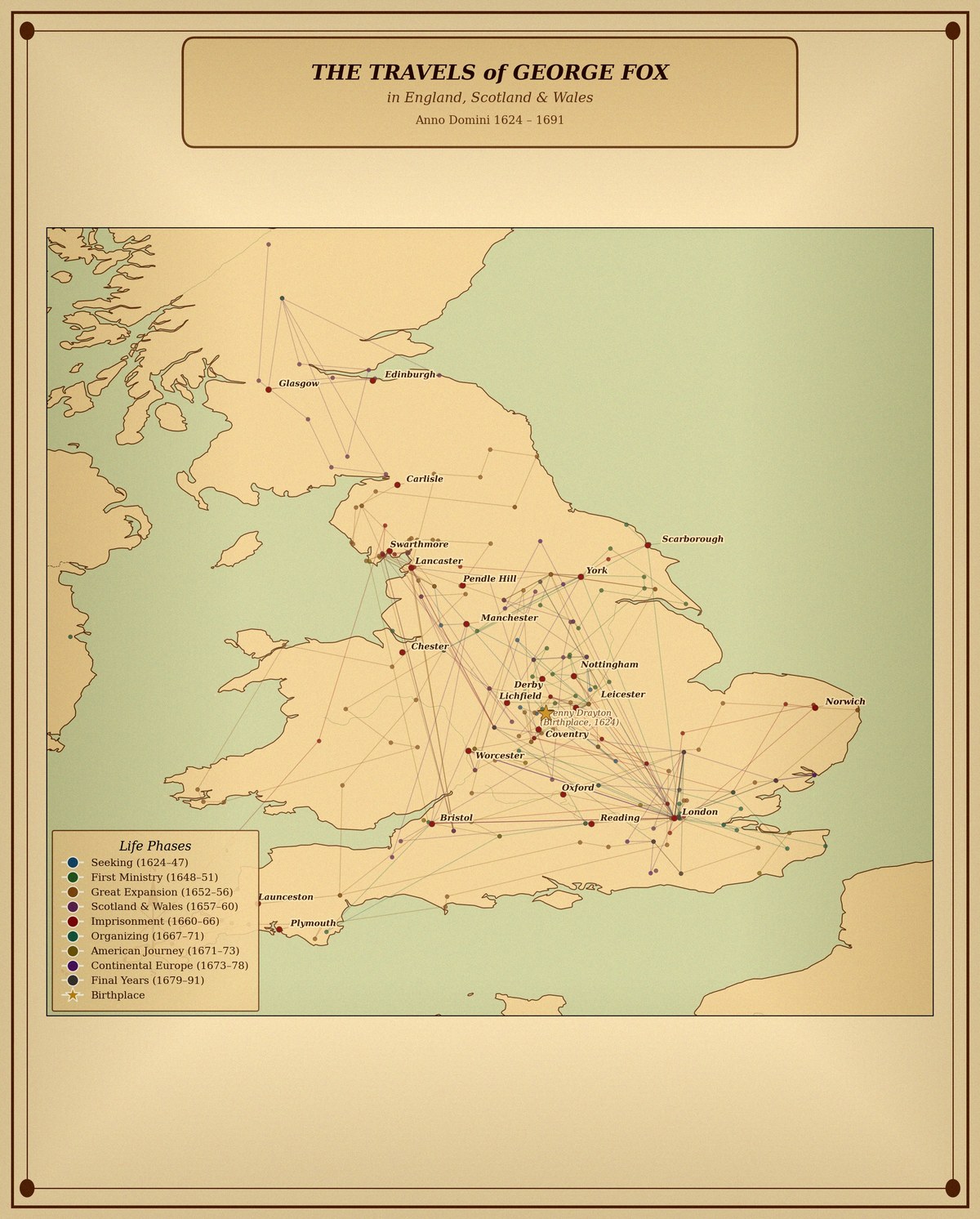

348 locations documented across three continents

412 travel points colour-coded by life phase • Gold star marks Fenny Drayton, his birthplace

Barbados, Jamaica & the American Colonies • Anno Domini 1671–1673

Holland & the Germanic Lands • Anno Domini 1677

Click any place name to view it on Google Maps

1624 – 1691 • 546 places documented

George Fox (1624–1691)

The Journal of George Fox is one of the great religious autobiographies, and has its place with the Confessions of St. Augustine, Saint Teresa's Life, Bunyan's Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners, the Life of Madam Guyon, Written by Herself, and John Wesley's Journal. The great interest which has developed in recent years in the Psychology of Religion, and in the study of mysticism, has most naturally given new interest and prominence to all autobiographical writings which lay bare the inward states and processes of the seeking, or the triumphant soul. Professor William James has stated a well-known fact when he says that religion must be studied in those individuals in whom it is manifested to an extra-normal degree. In other words, we must go to those individuals who have a genius for religion—for whom religion has constituted well nigh the whole of life. George Fox is eminently a character of this sort, as nearly every recent student of personal religion has recognized.

Then, again, his Journal is one of the best sources in existence for the historical study of the inner life of the Commonwealth and Restoration periods. There were few hamlets so obscure, few villages so remote that they did not have their streets traversed by this strange man in leather who always travelled with his eyes open. He knew all the sects and shades of religion which flourished in these prolific times. He never rides far without having some experience which shows the spirit and tendencies of the epoch. He never writes for effect, and he would have failed if he had tried, but he has, though utterly unconscious of it himself, filled his pages with the homely stuff out of which the common life of his England was made.

The world-events which moved rapidly across the stage during the crowded years of his activity receive but scant description from his pen. They are never told for themselves. They come in as by-products of a narrative whose main purpose is the story of personal inward experience. The camera is set for a definite object, but it catches the whole background with it. So here we have the picture of a sensitive soul, bent singly and solely on following a Divine Voice, yet its tasks are done, not in a desert, but in the setting of great historic events. Here are the soldiers of Marston Moor and Dunbar; Cromwell and his household; Desborough and Monk; the quartering of regicides and the "new era" under the second Charles. At every point we have vivid scenes in courts, in prisons, in churches, and in inns. People of all classes and sorts talk in their natural tongue in these pages. Fox has little dramatic power, but everything which furthers or hinders his earthly mission interests him and gets caught in his narrative. Pepys and Evelyn have readier pens, but Fox had many points of contact with the England of those days which they lacked.

In its original, unabridged form, the Journal contains many epistles and long, arid passages which are somewhat forbidding, and it has always required a patient, faithful reader. It has, however, always had a circle of readers outside the religious body which was founded by George Fox. This circle has been composed of those who were somewhat kindred in spirit with him, and the circle has kept small, mainly owing to the inherent difficulties of the ponderous, unedited mass of material. Of the Journal, in its complete form, there have nevertheless been thirteen editions published—nine in England and four in America.

The present editor has undertaken the task of abridging and editing it, in the belief that the time is ripe for such a work. The parts of the Journal which have been omitted—and they are many—have gone because they possess no living, present interest, or because they were repetitions of what is left. The story, as it stands, is continuous, and in no way suffers by omissions.

The writer of the Journal lacked perspective. Everything that came was equally important, and his first editors, in 1694, looked upon these writings as too precious and sacred to be tampered with or seriously condensed. The original manuscript, which has never been published (now in the possession of Charles James Spence, of North Shields, England), shows us that the little group of early editors contented themselves with improving the diction, introducing some system into the spelling, and cutting out an occasional anecdote which they feared might startle the sober reader. The original manuscript is a little livelier, fresher and more graphic than any published edition, though in the main we have in the editions a faithful reproduction of what Fox wrote.

The notes which attend the text in this edition have seemed necessary for a clear understanding of the passages to which they refer. They have been made as brief and as few in number as the situation would warrant. The Introduction is an attempt to put George Fox in his historical setting, and to develop the central ideas which he expounded, though all points of detail are postponed to the notes. This estimate of his religious message is based on a study of the body of his writings, which are voluminous, and on the writings of his contemporaries and fellow-laborers.

It is a pleasure for the editor to acknowledge the valuable assistance which he has received from his friends, Norman Penney, John Wilhelm Rowntree, Joshua Rowntree, and Prof. Allen C. Thomas. Among recent writers the following have been appreciative students of George Fox: Thomas Hodgkin, in his George Fox; Spurgeon, in his George Fox; Bancroft, in his History of America; Barclay, in his Inner Life of the Religious Societies of the Commonwealth; Arthur Gordon's Articles on George Fox in the Theological Review and in the Dictionary of National Biography; Frank Granger, in his The Soul of a Christian; Starbuck, author of Psychology of Religion; William James, in Varieties of Religious Experience; Josiah Royce, in The Mysticism of George Fox; Canon Curteis, Dissent in Its Relation to the English Church (see Chapter V, "The Quakers"); Westcott, Social Christianity (see pp. 119–133, "The Quakers"); and John Stephenson Rowntree, Two Lectures on George Fox.

William Penn (1644–1718)

There are mysterious moments in the early life of the individual which we call "budding periods." They are incubation crises, when some new power or function is coming into being. The budding tendency to creep, to walk, to imitate, or to speak is an indication that the psychological moment has come for learning the special operation. There are, too, similar periods in the history of the race—mysterious times of gestation, when something new is coming to be, however dimly the age itself comprehends the significance of its travail.

These racial "budding periods," like those others, have organic connection with the past. They are life-events which the previous history of humanity has made possible, and so they cannot be understood by themselves. The most notable characteristic of such times is the simultaneous outbreaking of new aspects of truth in sundered places and through diverse lives, as though the breath of a new Pentecost were abroad. This dawning time is generally followed by the appearance of some person who proves to be able to be the exponent of what others have dimly or subconsciously felt, and yet could not explicitly set forth. Such a person becomes by a certain divine right the prophet of the period because he knows how to interpret its ideas with such compelling force that he organizes men, either for action or for perpetuating the truth.

In the life history of the Anglo-Saxon people few periods are more significant than that which is commonly called the Commonwealth period, though the term must be used loosely to cover the span from 1640 to 1660. It was in high degree one of these incubation epochs when something new came to consciousness, and things equally new came to deed. This is not the place to describe the political struggles which finally produced tremendous constitutional changes, nor to tell how those who formed the pith and marrow of a nation rose against an antiquated conception of kingship and established principles of self-government.

The civil and political commotion was the outcome of a still deeper commotion. For a century the burning questions had been religious questions. The Church of that time was the result of compromise. It had inherited a large stock of medieval thought, and had absorbed a mass of medieval traditions. The men of moral and religious earnestness were bent on some measure of fresh reform. A spirit was abroad which could not be put down, and which would not be quiet. The old idea of an authoritative Church was outgrown, and yet no religious system had come in its place which provided for a free personal approach to God Himself. It has, in fact, always been a peculiarly difficult problem to discover some form of organization which will conserve the inherited truth and guarantee the stability of the whole, while at the same time it promotes the personal freedom of the individual.

The long struggle for religious reforms in England followed two lines of development. There was on the one hand a well-defined movement toward Presbyterianism, and on the other a somewhat chaotic search for freer religious life—a movement towards Independency. The rapid spread of Presbyterianism increased rather than diminished the general religious commotion. It soon became clear that this was another form of ecclesiastical authority, as inflexible as the old, and lacking the sacred sanction of custom. Then, too, the Calvinistic theology of the time did violence to human nature as a whole. Its linked logic might compel intellectual assent, but there is something in a man as real as his intellect which is not satisfied with this clamping of eternal truth into inflexible propositions. Personal soul-hunger, and the necessity which many individuals feel for spiritual quest, must always be reckoned with. It should not be forgotten that George Fox came to his spiritual crisis under this theology.

Thus while theology was stiffening into fixed form with one group, it was becoming ever more fluid among great masses of people throughout the nation. Religious authority ceased to count as it had in the past. Existing religious conditions were no longer accepted as final. There was a widespread restlessness which gradually produced a host of curious sects. Fox came directly in contact with at least four of the leading sectarian movements of the time, and there can be no question that they exerted an influence upon him both positively and negatively.

The first "sect" in importance, and the first to touch the life of George Fox, was the Baptist—at that time often called Anabaptist. His uncle Pickering was a member of this sect, and, though George seems to have been rather afraid of the Baptists, he must have learned something from them. They already had a long history, reaching back on the continent to the time of Luther, and their entire career had been marked by persecution and suffering. They were "Independents"—that is, they believed that Church and State should be separate, and that each local church should have its own independent life. They stoutly objected to infant baptism, maintaining that no act could have a religious value unless it were an act of will and of faith. Edwards, in his Gangraena (1646), reports a doctrine then afloat to the intent that "it is as lawful to baptize a cat, or a dog, or a chicken as to baptize an infant."

Their views on ministry were novel and must surely have interested Fox. They encouraged a lay ministry, and they actually had cobblers, leather-sellers, tailors, weavers, and at least one brewer preaching in their meetings. John Bunyan, who was of them, proved to general satisfaction that "Oxford and Cambridge were not necessary to fit men to preach." Still stranger, they had what their enemies scornfully called "She-preachers." Edwards recorded this dreadful error in his list of one hundred and ninety-nine "distinct errors, heresies and blasphemies": "Some say that 'tis lawful for women to preach, that they have gifts as well as men; and some of them do actually preach, having great resort to them"!

Furthermore, they held that all tithes and all set stipends were unlawful. They maintained that preachers should work with their own hands and not "go in black clothes." This sad error appears in Edwards's chaotic list: "It is said that all settled certain maintenance for ministers of the gospel is unlawful." Finally, many of the Baptists opposed the use of "steeple houses" and held the view that no person is fitted to preach or prophesy unless the Spirit moves him.

The "Seekers" are occasionally mentioned in the Journal and were widely scattered throughout England during the Commonwealth. They were serious-minded people who saw nowhere in the world any adequate embodiment of religion. They held that there was no true Church, and that there had been none since the days of the apostles. They did not celebrate any sacraments, for they held that there was nobody in the world who possessed an anointing clearly, certainly, and infallibly enough to perform such rites. They had no "heads" to their assemblies, for they had none among them who had "the power or the gift to go before one another in the way of eminency or authority." William Penn says that they met together "not in their own wills" and "waited together in silence, and as anything arose in one of their minds that they thought favored with a divine spring, so they sometimes spoke."

We are able to pick out a few of their characteristic "errors" from Edwards's list in the Gangraena: "That to read the Scriptures to a mixed congregation is dangerous." "That we did look for great matters from One crucified in Jerusalem 1600 years ago, but that does no good; it must be a Christ formed in us." "That men ought to preach and exercise their gifts without study and premeditation and not to think what they are to say till they speak, because it shall be given them in that hour and the Spirit shall teach them." "That there is no need of human learning or reading of authors for preachers, but all books and learning must go down. It comes from want of the Spirit that men write such great volumes."

The "Seekers" expected that the light was soon to break, the days of apostasy would end, and the Spirit would make new revelations. In the light of this expectation a peculiar significance attaches to the frequent assertion of Fox that he and his followers were living in the same Spirit which gave forth the Scriptures, and received direct commands as did the apostles. "I told him," says Fox of a "priest," "that to receive and go with a message, and to have a word from the Lord, as the prophets and apostles had and did, and as I had done, was quite another thing from ordinary experience."

A much more chaotic "sect" was that of the "Ranters." There was probably a small seed of truth in their doctrines, but under the excitement of religious enthusiasm they went to wild and perilous extremes, and in some cases even fell over the edge of sanity. They started with the belief that God is in everything, that every man is a manifestation of God, and they ended with the conclusion which their bad logic gave them that therefore what the man does God does. They were above all authority and actually said: "Have not we the Spirit, and why may not we write scriptures as well as Paul?" They believed the Scriptures "not because such and such writ it," but because they could affirm "God saith so in me." What Christ did was for them only a temporal figure, and nothing external was of consequence, since they had God Himself in them. As the law had been fulfilled they held that they were free from all law, and might without sin do what they were prompted to do. Richard Baxter says that "the horrid villainies of the sect did speedily extinguish it."

Judge Hotham told Fox in 1651 that "if God had not raised up the principle of Light and life which he (Fox) preached, the nation had been overrun with Ranterism." Many of the Ranters became Friends, some of them becoming substantial persons in the new Society, though there were for a time some serious Ranter influences at work within the Society, and a strenuous opposition was made to the establishment of discipline, order, and system.

The uprising of the "Fifth-monarchy men" is the only other movement which calls for special allusion. They were literal interpreters of Scripture, and had discovered grounds for believing in the near approach of the millennium. By some system of calculation they had concluded that the last of the four world monarchies—the Assyrian, Persian, Greek, and Roman—was tottering toward its fall, and the Fifth universal monarchy—Christ's—was about to be set up. The saints were to reign. The new monarchy was so slow in coming that they thought they might hasten it with carnal weapons. Perhaps a miracle would be granted if they acted on their faith. The miracle did not come, but the uprising brought serious trouble to Fox, who had before told these visionaries in beautifully plain language that "Christ has come and has dashed to pieces the four monarchies."

The person of genius discovers in the great mass of things about him just that which is vital and essential. He seizes the eternal in the temporal, and all that he borrows, he fuses with creative power into a new whole. This creative power belonged to George Fox. There was hardly a single truth in the Quaker message which had not been held by some one of the many sects of the time. He saw the spiritual and eternal element which was almost lost in the chaos of half truths and errors. In his message these scattered truths and ideas were fused into a new whole and received new life from his living central idea.

It is a strange fact that, though England had been facing religious problems of a most complex sort since the oncoming of the Reformation, it had produced no religious genius. No one had appeared who saw truth on a new level, or who possessed a personality and a personal message which compelled the attention of the nation. There had been long years of ingenious, patchwork compromise, but no distinct prophet. George Fox is the first real prophet of the English Reformation, for he saw what was involved in this great religious movement. Perhaps the most convincing proof of this is not the remarkable immediate results of his labors, though these are significant enough, but rather the easily-verified fact that the progress of religious truth during the last hundred years has been toward the truth which he made central in his message. However his age misunderstood him, he would today find a goodly fellowship of believers.

The purpose of this book is to have him tell his own story, which in the main he knows how to do. It will, however, be of some service to the reader to develop in advance the principle of which he was the exponent.

The first period of his life is occupied with a most painful quest for something which would satisfy his heart. His celebrated contemporary, Bunyan, possessed much greater power of describing inward states and experiences, but one is led to believe on comparing the two autobiographical passages that the sufferings of Fox, in his years of spiritual desolation, were even more severe than were those of Bunyan, though it is to be noted that the former does not suffer from the awful sense of personal sin as the latter does. "When I came to eleven years of age, I knew pureness and righteousness," is Fox's report of his own early deliverance from the sense of sin.

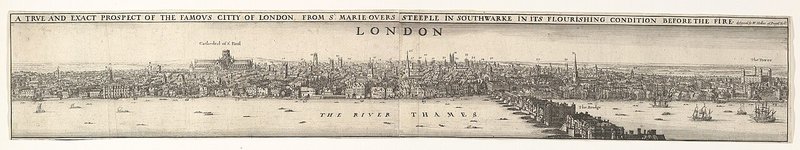

His "despair," from which he could find no comfort, was caused by the extreme sensitiveness of his soul. The discovery that the world, and even the Church, was full of wickedness and sin crushed him. "I looked upon the great professors of the city [London, 1643], and I saw all was dark and under the chain of darkness." This settled upon him with a weight, deep almost as death. Nothing in the whole world seemed to him so real as the world's wickedness. "I could have wished," he cries out, "I had never been born, or that I had been born blind that I might never have seen wickedness or vanity; and deaf that I might never have heard vain and wicked words, or the Lord's name blasphemed."

He was overwhelmed, however, not merely because he discovered that the world was wicked, but much more because he discovered that priests were "empty hollow casks," and that religion, as far as he could discover any in England, was weak and ineffective, with no dynamic message which moved with the living power of God behind it. He could find theology enough and theories enough, but he missed everywhere the direct evidence that men about him had found God. Religion seemed to him to be reduced to a system of clever substitutes for God, while his own soul could not rest until it found the Life itself.

The turning point of his life is the discovery—through what he beautifully calls an "opening"—that Christ is not merely a historic person who once came to the world and then forever withdrew, but that He is the continuous Divine Presence, God manifested humanly, and that this Christ can "speak to his condition." At first sight, there appears to be nothing epoch-making in these simple words. But it soon develops that what he really means is that he has discovered within the deeps of his own personality a meeting place of the human spirit with the Divine Spirit.

He had never had any doubts about the historical Christ. All that the Christians of his time believed about Christ, he, too, believed. His long search had not been to find out something about Christ, but to find Him. The Christ of the theological systems was too remote and unreal to be dynamic for him. Assent to all the propositions about Him left one still in the power of sin. He emerges from the struggle with an absolute certainty in his own mind that he has discovered a way by which his soul has immediate dealings with the living God.

The larger truth involved in his experience soon becomes plain to him, namely, that he has found a universal principle—that the Spirit of God reaches every man. He finds this divine-human relation taught everywhere in Scripture, but he challenges everybody to find the primary evidence of it in his own consciousness. He points out that every hunger of the heart, every dissatisfaction with self, every act of self-condemnation, every sense of shortcoming shows that the soul is not unvisited by the Divine Spirit. To want God at all implies some acquaintance with Him. The ability to appreciate the right, to discriminate light from darkness, the possibility of being anything more than a creature of sense, living for the moment, means that our personal life is in contact at some point with the Infinite Life, and that all things are possible to him who believes and obeys.

To all sorts and conditions of men, Fox continually makes appeal to "that of God" within them. At other times he calls it indiscriminately the "Light," or the "Seed," or the "Principle" of God within the man. Frequently it is the "Christ within." In every instance he means that the Divine Being operates directly upon the human life, and the new birth, the real spiritual life, begins when the individual becomes aware of Him and sets himself to obey Him. He may have been living along with no more explicit consciousness of a Divine presence than the bubble has of the ocean on which it rests and out of which it came; but even so, God is as near him as is the beating of his own heart, and only needs to be found and obeyed.

Instead of making him undervalue the historic revelations of God, the discovery of this principle of truth gave him a new insight into the revelations of the past and the supreme manifestations of the Divine Life and Love. He could interpret his own inward experience in the light of the gathered revelation of the ages. His contemporaries used to say that, though the Bible were lost, it might be found in the mouth of George Fox, and there is not a line in the Journal to indicate that he undervalued either the Holy Scriptures or the historic work of Christ for human salvation. Entirely the contrary.

As soon as he realized that the same God who spoke directly to men in earlier ages still speaks directly, and that to be a man means to have a "seed of God" within, he saw that there were no limits to the possibilities of a human life. It becomes possible to live entirely in the power of the Spirit and to have one's life made a free and victorious spiritual life. So to live is to be a "man"—for sin and disobedience reduce a man. The normal person, then, is the one who has discovered the infinite Divine resources, and is turning them into the actual stuff of a human life. That it happens now and then is no mystery; that it happens so seldom is the real mystery. "I asked them if they were living in the power of the Spirit that gave forth the Scriptures" is his frequent and somewhat naïve question, as though everybody ought to be doing it.

The consciousness of the presence of God is the characteristic thing in George Fox's religious life. His own life is in immediate contact with the Divine Life. It is this conviction which unifies and gives direction to all his activities. God has found him and he has found God. It is this experience which puts him among the mystics.

But here we must not overlook the distinction in types of mysticism. There is a great group of mystics who have painfully striven to find God by a path of negation. They believe that everything finite is a shadow, an illusion—nothing real. To find God, then, every vestige of the finite must be given up. The infinite can be reached only by wiping out all marks of the finite. The Absolute can be attained only when every "thing" and every "thought" have been reduced to zero. But the difficulty is that this kind of an Absolute becomes absolutely unknowable. From the nature of the case He could not be found, for to have any consciousness of Him at all would be to have a finite and illusory thought.

George Fox belongs rather among the positive mystics, who seek to realize the presence of God in this finite human life. That He transcends all finite experiences they fully realize, but the reality of any finite experience lies just in this fact, that the living God is in it and expresses some divine purpose through it, so that a man may, as George Fox's friend Isaac Penington says, "become an organ of the life and power of God," and "propagate God's life in the world." The mystic of this type may feel the light break within him and know that God is there, or he may equally well discover Him as he performs some clear, plain duty which lies across his path. His whole mystical insight is in his discovery that God is near, and not beyond the reach of the ladders which He has given us.

But no one has found the true George Fox when he stops with an analysis of the views which he held. Almost more remarkable than the truth which he proclaimed was the fervor, the enthusiasm, the glowing passion of the man. He was of the genuine apostolic type. He had come through years of despair over the wickedness of the world, but as soon as the Light really broke, and he knew that he had a message for the world in its sin and ignorance, there was after that nothing but the grave itself which could keep him quiet. He preached in cathedrals, on hay stacks, on cliffs of rock, from hill tops, under apple trees and elm trees, in barns and in city squares, while he sent epistles from every prison in which he was shut up. Wherever he could find men who had souls to save he told them of the life and Truth which he had found.

Whether one is in sympathy with Fox's mystical view of life or not, it is impossible not to be impressed with the practical way in which he wrought out his faith. After all, the view that God and man are not isolated was not new; the really new thing was the appearance of a man who genuinely practiced the Divine presence and lived as though he knew that his life was in a Divine environment.

We have dwelt upon the fundamental religious principle of Fox at some length, because his great work as a social reformer and as the organizer of a new system of Church government proceeds from this root principle. One central idea moves through all he did. His originality lies, however, not so much in the discovery, or the rediscovery, of the principle as in the fearless application of it. Other men had believed in Divine guidance; other Christians had proclaimed the impenetration of God in the lives of men. But George Fox had the courage to carry his conviction to its logical conclusions. He knew that there were difficulties entailed in calling men everywhere to trust the Light and to follow the Voice, but he believed that there were more serious difficulties to be faced by those who put some external authority in the place of the soul's own sight. He was ready for the consequences and he proceeded to carry out both in the social and in the religious life of his time the experiment of obeying the Light within. It is this courageous fidelity to his insight that made him a social reformer and a religious organizer. He belongs, in this respect, in the same list with St. Francis of Assisi. They both attempted the difficult task of bringing religion from heaven to earth.

1. The Divine Right of Man. In the light of his religious discovery Fox reinterpreted man as a member of society. If man has direct intercourse with God he is to be treated with noble respect. He met the doctrine of the divine right of kings with the conviction of the divine right of man. Every man is to be treated as a man. He was a leveler, but he leveled up, not down. Every man was to be read in terms of his possibilities—if not of royal descent, certainly of royal destiny. This view made Fox an unparalleled optimist. He believed that a mighty transformation would come as soon as men were made aware of this divine relationship which he had discovered. They would go to living as he had done, in the power of this conviction.

He began at once to put in practice his principle of equality—that is, equality of privilege. He cut straight through the elaborate web of social custom which hid man's true nature from himself. Human life had become sicklied o'er with a cast of sham, until man had half forgotten to act as man. Fox rejected for himself every social custom which seemed to him to be hollow and to belittle man himself. The honor which belonged to God he would give to no man, and the honor which belonged to any man he gave to every man. This was the reason for his "thee" and "thou." The plural form had been introduced to give distinction. He would not use it. The Lord Protector and the humble cotter were addressed alike. He had an eye for the person of great gifts and he never wished to reduce men to indistinguishable atoms of society, but he was resolved to guard the jewel of personality in every individual—man or woman.

2. A Reformer for Human Rights. His estimate of the worth of man made him a reformer. In society as he found it men were often treated more as things than as persons. For petty offenses they were hung, and if they escaped this fate they were put into prisons, where no touch of man's humanity was in evidence. In the never-ending wars the common people were hardly more than human dice. Their worth as men was well nigh forgotten. Trade was conducted on a system of sliding prices—high for this man, low for some other. Dealers were honest where they had to be; dishonest where they could be. The courts of justice were extremely uncertain and irregular, as the pages of this Journal continually show.

Against every such crooked system which failed to recognize the divine right of man George Fox set himself. He himself had large opportunities of observing the courts of justice and the inhuman pens which by courtesy were called jails. But he became a reformer, not to secure his own rights or to get a better jail to lie in, but to establish the principle of human rights for all men. He went calmly to work to carry an out-and-out honesty into all trade relations, to establish a fixed price for goods of every sort, to make principles of business square with principles of religion. By voice or by epistle he called every judge in the realm to "mind that of God" within him. He refused ever to take an oath, because he was resolved to make a plain man's "yea" weigh as heavy as an oath. He was always in the lists against the barbarity of the penal system, the iniquity of enslaving men, the wickedness of war, the wastefulness of fashion, and the evils of drunkenness, and by argument and deed he undertook to lead the way to a new heroism, better than the heroism of battlefields.

3. The Value of Education. The logic of his principle compelled him to value education. If all men are to count as men, it is a man's primal duty to be all he can be. To be a poor organ of God when one was meant for a good one belongs among the high sins. If it was "opened" to him that Oxford and Cambridge could not make men ministers, his own reason taught him that it is not safe to call all men to obey the voice and follow the light without broad-basing them at the same time in the established facts of history and nature. Fox himself very early set up schools for boys and girls alike in which "everything civil and useful in creation" was to be taught. It is, however, quite possible that he undervalued the aesthetic side of man, and that he suffered by his attempt to starve it. In this particular he shared the puritan tendency, and had not learned how to hold all things in proportion, and to make the culture of the senses at the same time beautify the inner man.

4. A New Interpretation of Worship. On the distinctively religious side his discovery of a direct divine-human relationship led to a new interpretation of worship and ministry. God is not far off. He needs no vicar, no person of any sort between Himself and the worshipper. Grace no more needs a special channel than the dew does. There is no special holy place, as though God were more there than here. He does not come from somewhere else. He is Spirit, and needs only a responsive soul, an open heart, to be found. Worship properly begins when the soul discovers Him and enjoys His presence—in the simplest words it is the soul's appreciation of God.

With his usual optimism, he believed that all men and women were capable of this stupendous attainment. He threw away all crutches at the start and called upon everybody to walk in the Spirit, to live in the Light. His house of worship was bare of everything but seats. It had no shrine, for the shekinah was to be in the hearts of those who worshipped. It had no altar, for God needed no appeasing, seeing that He Himself had made the sacrifice for sin. It had no baptismal font, for baptism was in his belief nothing short of immersion into the life of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—a going down into the significance of Christ's death and a coming up in newness of life with Him. There was no communion table, because he believed that the true communion consisted in partaking directly of the soul's spiritual bread—the living Christ. There were no confessionals, for in the silence, with the noise and din of the outer life hushed, the soul was to unveil itself to its Maker and let His light lay bare its true condition. There was no organ or choir, for each forgiven soul was to give praise in the glad notes that were natural to it. No censer was swung, for he believed God wanted only the fragrance of sincere and prayerful spirits. There was no priestly mitre, because each member of the true Church was to be a priest unto God. No official robes were in evidence, because the entire business of life, in meeting and outside, was to be the putting on of the white garments of a saintly life. From beginning to end worship was the immediate appreciation of God, and the appropriate activity of the whole being in response to Him.

William Penn says of him: "The most awful, living, reverent frame I ever felt or beheld was his in prayer." And this was because he realized that he was in the presence of God when he prayed.

He believed that the ministry of truth is limited to no class of men and to no sex. As fast and as far as any man discovers God it becomes his business to make Him known to others. His ability to do this effectively is a gift from God, and makes him a minister. The only thing the Church does is to recognize the gift. This idea carried with it perfect freedom of utterance to all who felt a call to speak, a principle which has worked out better than the reader would guess, though it has been often sorely tested. In the Society which he founded there was no distinction of clergy and laity. He undertook the difficult task of organizing a Christian body in which the priesthood of believers should be an actual fact, and in which the ordinary religious exercises of the Church should be under the directing and controlling power of the Holy Spirit manifesting itself through the congregation.

Not the least service of Fox to his age was the important part which he took in breaking down the intolerable doctrine of predestination, which hung like an incubus over men's lives. It threw a gloom upon every person who found himself forced by his logic to believe it, and its effect upon sensitive souls was simply dreadful. Fox met this doctrine with argument, but he met it also with something better than argument—he set over against it two facts: that Divine grace and light are free, and that an inward certainty of God's favor and acceptance is possible for every believer. Wherever Quakerism went this inward assurance went with it. The shadow of dread uncertainty gave place to sunlight and joy. This was the beginning of a spiritual emancipation which is still growing, and peaceful faces and fragrant lives are the result.

No reader of the Journal can fail to be impressed with the fact that George Fox believed himself to be an instrument for the manifestation of miraculous power. Diseases were cured through him; he foretold coming events; he often penetrated states and conditions of mind and heart; he occasionally had a sense of what was happening in distant parts, and he himself underwent on at least three occasions striking bodily changes, so that he seemed, for days at a time, like one dead, and was in one of these times incapable of being bled. These passages need trouble no one, nor need their truthfulness be questioned. He possessed an unusual psychical nature, delicately organized, capable of experiences of a novel sort, but such as are today very familiar to the student of psychical phenomena. The marvel is that with such a mental organization he was so sane and practical, and so steadily kept his balance throughout a life which furnished numerous chances for shipwreck.

It is very noticeable—rather more so in the complete Journal than in this Autobiography—that "judgments" came upon almost everybody who was a malicious opposer of him or his work. "God cut him off soon after" is a not infrequent phrase. It is manifestly impossible to investigate these cases now, and to verify the facts, but the well-tested honesty of the early Friends leaves little ground for doubting that the facts were substantially as they are reported. Fox's own inference that all these persons had misfortune as a direct "judgment" for having harmed him and hindered his cause will naturally seem to us a too hasty conclusion. It is not at all strange that in this eventful period many persons who had dealings with him should have suffered swift changes of fortune, and of course he failed to note how many there were who did not receive judgment in this direct manner. One regrets, of course, that this kindly spiritual man should have come so near enjoying what seemed to him a divine vengeance upon his enemies, but we must remember that he believed in his soul that his work was God's work, and hence to frustrate it was serious business.

He founded a Society, as he called it, which he evidently hoped, and probably believed, would sometime become universal. The organization in every aspect recognized the fundamentally spiritual nature of man. Every individual was to be a vital, organic part of the whole; free, but possessed of a freedom which had always to be exercised with a view to the interests and edification of the whole. It was modelled exactly on the conception of Paul's universal Church of many members, made a unity not from without, but by the living presence of the One Spirit.

All this work of organization was effected while Fox himself was in the saddle, carrying his message to town after town, interrupted by long absences in jail and dungeon, and steadily opposed by the fanatical antinomian elements which had flocked to his standard. It is not the least mark of his genius that in the face of an almost unparalleled persecution he left his fifty thousand followers in Great Britain and Ireland formed into a working and growing body, with equally well-organized meetings in Holland, New England, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas.

His personality and his message had won men from every station of life, and if the rank and file were from the humbler walks, there were also men and women of scholarship and fame. Robert Barclay, from the schools of Paris, gave the new faith its permanent expression in his Apology. William Penn worked its principles out in a holy experiment in a Christian Commonwealth, and Isaac Penington, in his brief essays, set forth in rich and varied phrase the mystical truth which was at the heart of the doctrine.

This is the place for exposition, not for criticism. It requires no searchlight to reveal in this man the limitations and imperfections which his age and his own personal peculiarities fixed upon him. He saw in part and he prophesied in part. But, like his great contemporary, Cromwell, he had a brave sincerity, a soul absolutely loyal to the highest he saw. The testimony of the Scarborough jailer is as true as it is unstudied—"as stiff as a tree and as pure as a bell." It is fitting that this study of him should close with the words of the man who knew him best—William Penn: "I write my knowledge and not report, and my witness is true, having been with him for weeks and months together on diverse occasions, and those of the nearest and most exercising nature, by sea and land, in this country and in foreign countries; and I can say I never saw him out of his place, or not a match for every service or occasion. For in all things he acquitted himself like a man, yea, a strong man, a new and heavenly-minded man; a divine and a naturalist, and all of God Almighty's making."

William Penn (1644–1718)

The blessed instrument of and in this day of God, and of whom I am now about to write, was George Fox, distinguished from another of that name by that other's addition of "younger" to his name in all his writings—not that he was so in years, but that he was so in the truth. But he was also a worthy man, witness, and servant of God in his time.

But this George Fox was born in Leicestershire, about the year 1624. He descended of honest and sufficient parents, who endeavored to bring him up, as they did the rest of their children, in the way and worship of the nation—especially his mother, who was a woman accomplished above most of her degree in the place where she lived. But from a child he appeared of another frame of mind than the rest of his brothers and sisters, being more religious, inward, still, solid, and observing beyond his years, as the answers he would give and the questions he would put upon occasion manifested, to the astonishment of those that heard him, especially in divine things.

His mother, taking notice of his singular temperament and the gravity, wisdom, and piety that very early shone through him—refusing childish and vain sports and company when very young—she was tender and indulgent over him, so that from her he met with little difficulty. As to his employment, he was brought up in country business; and as he took most delight in sheep, so he was very skillful in them—an employment that very well suited his mind in several respects, both for its innocence and solitude, and was a fitting figure of his later ministry and service.

I shall not break in upon his own account, which is by much the best that can be given; and therefore I desire, what I can, to avoid saying anything of what is said already, as to the particular passages of his coming forth. But in general, when he was somewhat above twenty, he left his friends and visited the most retired and religious people. There were some at that time in this nation, especially in those parts, who waited for the consolation of Israel night and day, as Zacharias, Anna, and good old Simeon did of old time (Luke 2:25–38). To these he was sent, and these he sought out in the neighboring counties, and among them he sojourned till his more ample ministry came upon him.

At this time he taught, and was an example of, silence—endeavoring to bring people from self-performances, testifying and turning them to the light of Christ within them, and encouraging them to wait in patience to feel the power of it stir in their hearts, that their knowledge and worship of God might stand in the power of an endless life, which was to be found in the light as it was obeyed in its manifestation in man. For "In him was life; and the life was the light of men" (John 1:4). Life in the Word, light in men, and life too, as the light is obeyed; the children of the light living by the life of the Word, by which the Word begets them again to God—which is the regeneration and new birth, without which there is no coming into the kingdom of God (John 3:3–5). And whoever comes to this is greater than John—that is, greater than John's ministry, which was not that of the kingdom, but the consummation of the legal dispensation and the opening of the gospel dispensation (Matthew 11:11).

Accordingly, several meetings were gathered in those parts, and thus his time was employed for some years.

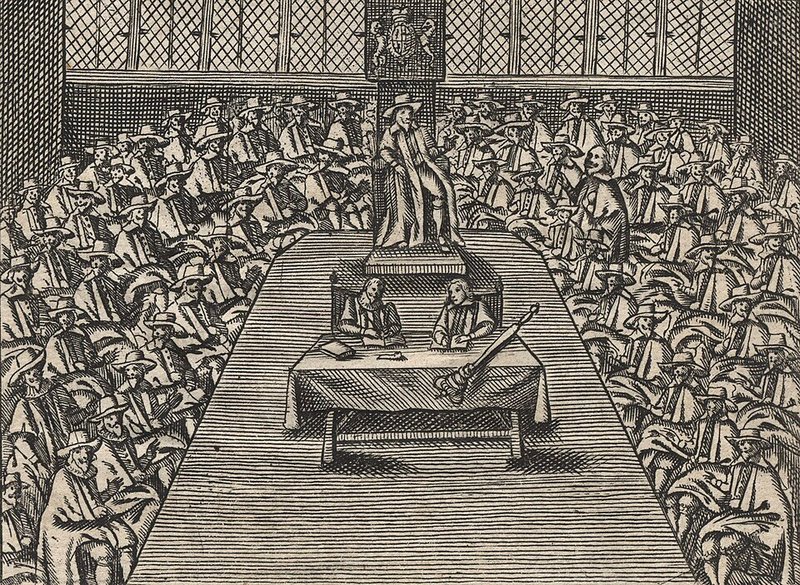

In 1652, while he was in his usual retirement to the Lord upon a very high mountain in some of the hither parts of Yorkshire (as I take it), his mind exercised towards the Lord, he had a vision of the great work of God in the earth, and of the way that he was to go forth to begin it. He saw people as thick as motes in the sun, that should in time be brought home to the Lord, that there might be but "one fold, and one shepherd" (John 10:16) in all the earth. There his eye was directed northward, beholding a great people that should receive him and his message in those parts.

Upon this mountain he was moved of the Lord to sound out his great and notable day, as if he had been in a great auditorium. And from there he went north, as the Lord had shown him; and in every place where he came—if not before he came to it—he had his particular exercise and service shown to him, so that the Lord was his leader indeed. For it was not in vain that he travelled; God in most places sealed his commission with the convincement of some of all sorts, as well publicans as sober professors of religion.

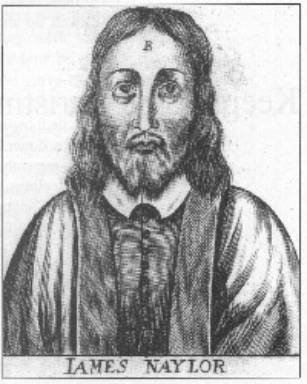

Some of the first and most eminent of them, which are at rest, were Richard Farnsworth, James Nayler, William Dewsbury, Francis Howgill, Edward Burrough, John Camm, John Audland, Richard Hubberthorn, T. Taylor, John Aldam, T. Holmes, Alexander Parker, William Simpson, William Caton, John Stubbs, Robert Widders, John Burnyeat, Robert Lodge, Thomas Salthouse, and many more worthies that cannot be well here named, together with many yet living of the first and great convincement. After the knowledge of God's purging judgments in themselves, and some time of waiting in silence upon Him to feel and receive power from on high to speak in His name (which none else rightly can, though they may use the same words), they felt the divine motions and were frequently drawn forth—especially to visit the public assemblies—to reprove, inform, and exhort them, sometimes in markets, fairs, streets, and by the highway side, calling people to repentance and to turn to the Lord with their hearts as well as their mouths, directing them to the light of Christ within them to see, examine, and consider their ways by, and to "eschew evil, and do good" (Psalm 34:14; 1 Peter 3:11).

And they suffered great hardships for this their love and good will, being often stocked, stoned, beaten, whipped, and imprisoned—though honest men and of good report where they lived—who had left wives and children, and houses and lands, to visit them with a living call to repentance. And though the priests generally set themselves to oppose them and write against them, and insinuated most false and scandalous stories to defame them, stirring up the magistrates to suppress them (especially in those northern parts), yet God was pleased so to fill them with His living power and give them such an open door of utterance in His service that there was a mighty convincement over those parts.

And through the tender and singular indulgence of Judge Bradshaw and Judge Fell, in the infancy of things, the priests were never able to gain the point they labored for, which was to have proceeded to blood and, if possible, Herod-like, by a cruel exercise of the civil power, to have cut them off and rooted them out of the country. Especially Judge Fell, who was not only a check to their rage in the course of legal proceedings, but otherwise upon occasion, and finally countenanced this people. For his wife receiving the truth with the first, it had that influence upon his spirit—being a just and wise man, and seeing in his own wife and family a full confutation of all the popular clamors against the way of truth—that he covered them what he could, and freely opened his doors and gave up his house to his wife and her friends, not valuing the reproach of ignorant or evil-minded people. I mention this here to his and her honor, and it will be, I believe, an honor and a blessing to such of their name and family as shall be found in that tenderness, humility, love, and zeal for the truth and people of the Lord.

That house was for some years at first—until the truth had opened its way in the southern parts of this island—an eminent gathering place of this people. Others of good note and substance in those northern counties had also opened their houses with their hearts to the many publishers that in a short time the Lord had raised to declare His salvation to the people, and where meetings of the Lord's messengers were frequently held, to communicate their services and exercises, and comfort and edify one another in their blessed ministry.

But lest this may be thought a digression, having touched upon this before, I return to this excellent man. And for his personal qualities, both natural, moral, and divine, as they appeared in his conversations with his brothers and sisters in the faith and in the church of God, take as follows.

He was a man that God endowed with a clear and wonderful depth, a discerner of others' spirits, and very much a master of his own. And though the side of his understanding which lay next to the world, and especially the expression of it, might sound uncouth and unfashionable to refined ears, his matter was nevertheless very profound, and would not only bear to be often considered, but the more it was so, the more weighty and instructing it appeared. And as abruptly and brokenly as sometimes his sentences would fall from him about divine things, it is well known they were often as texts to many fairer declarations.

And indeed it showed beyond all contradiction that God sent him, that no arts or education had any share in the matter or manner of his ministry, and that so many great, excellent, and necessary truths as he came forth to preach to mankind had therefore nothing of man's wit or wisdom to recommend them. So that as to man he was an original, being no man's copy. And his ministry and writings show they are from one that was not taught of man, nor had learned what he said by study. Nor were they notional or speculative, but sensible and practical truths, tending to conversion and regeneration and the setting up the kingdom of God in the hearts of men—and the way of it was his work.

So that I have many times been overcome in myself, and been made to say with my Lord and Master upon the like occasion, "I thank thee, O Father, Lord of heaven and earth, because thou hast hid these things from the wise and prudent, and hast revealed them unto babes" (Matthew 11:25). For many times has my soul bowed in a humble thankfulness to the Lord, that He did not choose any of the wise and learned of this world to be the first messenger in our age of His blessed truth to men, but that He took one that was not of high degree or elegant speech or learned after the way of this world, that His message and work He sent him to do might come with less suspicion or jealousy of human wisdom and interest, and with more force and clearness upon the consciences of those that sincerely sought the way of truth in the love of it.

I say, beholding with the eye of my mind, which the God of heaven had opened in me, the marks of God's finger and hand visibly in this testimony—from the clearness of the principle, the power and efficacy of it in the exemplary sobriety, plainness, zeal, steadiness, humility, gravity, punctuality, charity, and circumspect care in the government of church affairs, which shone in his and their life and testimony that God employed in this work—it greatly confirmed me that it was of God, and engaged my soul in a deep love, fear, reverence, and thankfulness for His love and mercy therein to mankind. In which mind I remain, and shall, I hope, to the end of my days.

In his testimony or ministry he labored much to open truth to the people's understandings, and to ground them upon the principle and principal, Christ Jesus, "the light of the world" (John 8:12), so that by bringing them to something that was of God in themselves, they might the better know and judge of Him and themselves.

He had an extraordinary gift in opening the Scriptures. He would go to the marrow of things, and show the mind, harmony, and fulfilling of them with much plainness, and to great comfort and edification. The mystery of the first and second Adam, of the fall and restoration, of the law and gospel, of shadows and substance, of the servant and son's state, and the fulfilling of the Scriptures in Christ—and by Christ the true light in all that are His, through the obedience of faith—were much of the substance and drift of his testimonies. In all which he was witnessed to be of God, being sensibly felt to speak that which he had received of Christ, and was his own experience in that which never errs nor fails.

But above all he excelled in prayer. The inwardness and weight of his spirit, the reverence and solemnity of his address and behavior, and the fewness and fullness of his words have often struck even strangers with admiration, as they used to reach others with consolation. The most awful, living, reverent frame I ever felt or beheld, I must say, was his in prayer. And truly it was a testimony that he knew and lived nearer to the Lord than other men; for "they that know him most will see most reason to approach him with reverence and fear".

He was of an innocent life, no busybody, nor self-seeker, neither touchy nor critical. What fell from him was very inoffensive, if not very edifying. So meek, contented, modest, easy, steady, tender, it was a pleasure to be in his company. He exercised no authority but over evil, and that everywhere and in all, but with love, compassion, and long-suffering. A most merciful man, as ready to forgive as unlikely to take or give offense. Thousands can truly say he was of an excellent spirit and savor among them, and because of this the most excellent spirits loved him with an unfeigned and unfading love.

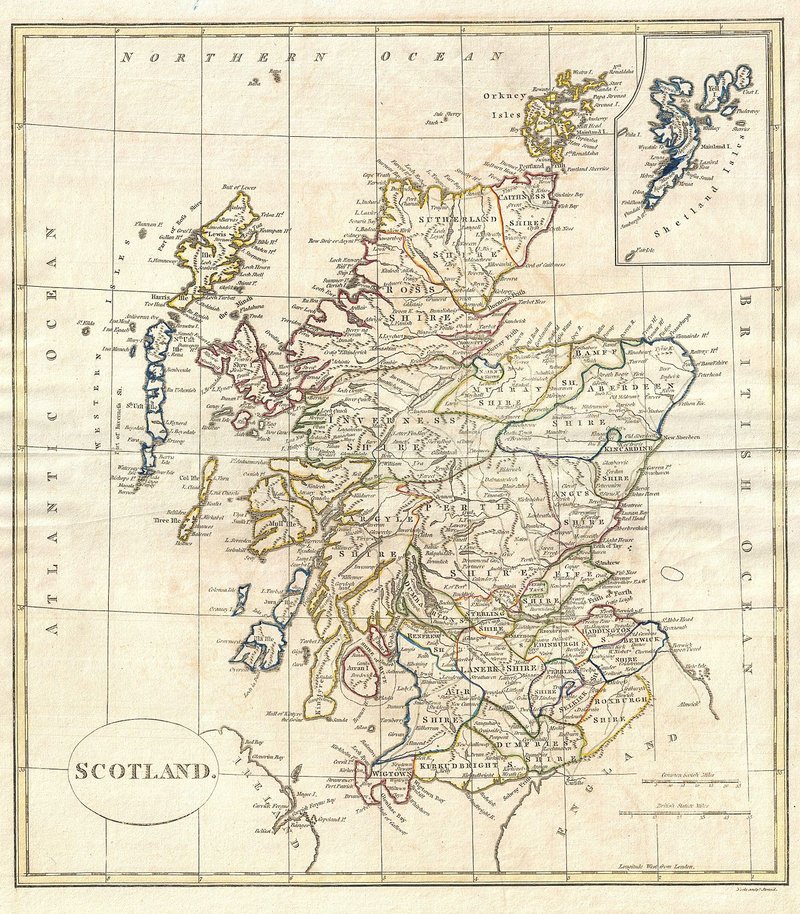

He was an incessant laborer. For in his younger time, before his many great and deep sufferings and travels had weakened his body for itinerant services, he labored much in the word and doctrine and discipline in England, Scotland, and Ireland, turning many to God and confirming those that were convinced of the truth, and settling good order as to church affairs among them. And towards the conclusion of his travelling services, between the years 1671 and 1677, he visited the churches of Christ in the plantations in America, and in the United Provinces and Germany, as his following Journal relates, to the convincement and consolation of many.

After that time he chiefly resided in and about the city of London. And besides the services of his ministry, which were frequent, he wrote much both to them that are within and those that are without the communion. But the care he took of the affairs of the church in general was very great. He was often where the records of the affairs of the church are kept, and the letters from the many meetings of God's people over all the world, where settled, come upon occasions. These letters he had read to him and communicated them to the meeting that is weekly held there for such services. He would be sure to stir them up to discharge them, especially in suffering cases—showing great sympathy and compassion upon all such occasions, carefully looking into the respective cases and endeavoring speedy relief according to the nature of them, so that the churches and any of the suffering members were sure not to be forgotten or delayed in their desires if he were there.

As he was unwearied, so he was undaunted in his services for God and His people. He was no more to be moved to fear than to wrath. His behavior at Derby, Lichfield, Appleby, before Oliver Cromwell, at Launceston, Scarborough, Worcester, and Westminster Hall, with many other places and exercises, did abundantly evidence it to his enemies as well as his friends.

But as in the primitive times some rose up against the blessed apostles of our Lord Jesus Christ, even from among those that they had turned to the hope of the gospel, and who became their greatest trouble, so this man of God had his share of suffering from some that were convinced by him. Through prejudice or mistake they ran against him as one that sought dominion over conscience, because he pressed, by his presence or epistles, a ready and zealous compliance with such good and wholesome things as tended to an orderly conduct about the affairs of the church and in their walking before men.

That which contributed much to this ill work was in some a begrudging of this meek man the love and esteem he had and deserved in the hearts of the people, and weakness in others that were taken with their groundless suggestions of imposition and blind obedience. They would have had every man independent, that as he had the principle in himself, he should only stand and fall to that and nobody else—not considering that the principle is one in all. And though the measure of light or grace might differ, yet the nature of it was the same; and being so, they struck at the spiritual unity which a people guided by the same principle are naturally led into. So that what is evil to one is so to all, and what is virtuous, honest, and of good report to one is so to all, from the sense and savor of the one universal principle which is common to all, and which (as the disaffected professed it to be) is the root of all true Christian fellowship, and that spirit into which the people of God drink and come to be "spiritually minded" (Romans 8:6), and of "one heart and one soul" (Acts 4:32).

Some weakly mistook good order in the government of church affairs for discipline in worship, and thought that it was so pressed or recommended by him and other brethren. And they were ready to reflect the same things that dissenters had very reasonably objected upon the national churches, that had coercively pressed conformity to their respective creeds and worships—whereas these things related wholly to conduct, and the outward and (as I may say) civil part of the church, that men should walk up to the principles of their belief and not be wanting in care and charity.

But though some have stumbled and fallen through mistakes and an unreasonable obstinacy, even to a prejudice, yet blessed be God, the generality have returned to their first love, and seen the work of the enemy, who loses no opportunity or advantage by which he may check or hinder the work of God and disquiet the peace of His church and chill the love of His people to the truth and to one another. And there is hope of many that are yet at a distance.

In all these occasions, though there was no person the discontented struck so sharply at as this good man, he bore all their weakness and prejudice, and returned not reflection for reflection, but forgave them their weak and bitter speeches, praying for them that they might have a sense of their hurt and see the subtlety of the enemy to rend and divide, and return into their first love that thought no ill. And truly, I must say that though God had visibly clothed him with a divine preference and authority, and indeed his very presence expressed a religious majesty, yet he never abused it, but held his place in the church of God with great meekness and a most engaging humility and moderation.

For upon all occasions, like his blessed Master, he was "a servant to all" (Mark 10:44), holding and exercising his eldership in the invisible power that had gathered them, with reverence to the Head and care over the body. And he was received only in that spirit and power of Christ, as the first and chief elder in this age, who—as he was therefore worthy of "double honour" (1 Timothy 5:17)—so for the same reason it was given by the faithful of this day, because his authority was inward and not outward, and he got it and kept it by the love of God and "power of an endless life" (Hebrews 7:16).

I write my knowledge and not report, and my witness is true, having been with him for weeks and months together on many occasions, and those of the nearest and most exercising nature, and that by night and by day, by sea and by land, in this and in foreign countries. And I can say I never saw him out of his place, or not a match for every service or occasion. For in all things he acquitted himself like a man—yes, a strong man, a new and heavenly-minded man. A divine, and a naturalist, and all of God Almighty's making.

I have been surprised at his questions and answers in natural things, that while he was ignorant of useless and sophistical science, he had in him the foundation of useful and commendable knowledge, and cherished it everywhere. Civil beyond all forms of breeding in his behavior; very temperate, eating little and sleeping less, though a bulky person.

Thus he lived and sojourned among us, and as he lived so he died, feeling the same eternal power that had raised and preserved him in his last moments. So full of assurance was he that he triumphed over death; and so even to the last, as if death were hardly worth notice or a mention—recommending to some with him the dispatch and distribution of an epistle just before written to the churches of Christ throughout the world, and his own books; but above all, Friends, and of all Friends those in Ireland and America, twice over, saying, "Mind poor Friends in Ireland and America."

And to some that came in and inquired how he found himself, he answered, "Never heed; the Lord's power is over all weakness and death. The Seed reigns; blessed be the Lord." This was about four or five hours before his departure out of this world. He was at the great meeting near Lombard Street on the first day of the week, and it was the third following, about ten at night, when he left us, being at the house of H. Goldney in the same court.

In a good old age he went, after having lived to see his children's children to several generations in the truth. He had the comfort of a short illness and the blessing of a clear sense to the last. And we may truly say with a man of God of old, that "he being dead yet speaketh" (Hebrews 11:4). And though absent in body, he is present in spirit—neither time nor place being able to interrupt the communion of saints, or dissolve the fellowship of the spirits of the just.

His works praise him, because they are to the praise of Him that worked by him; for which his memorial is and shall be blessed. I have done, as to this part of my preface, when I have left this short epitaph to his name: "Many daughters have done virtuously, but thou excellest them all" (Proverbs 31:29).

George Fox (1624–1691) — Founder of the Society of Friends

That all may know the dealings of the Lord with me, and the various exercises, trials, and troubles through which He led me in order to prepare and fit me for the work to which He had appointed me, and may thereby be drawn to admire and glorify His infinite wisdom and goodness, I think fit (before I proceed to set forth my public travels in the service of Truth) briefly to mention how it was with me in my youth, and how the work of the Lord was begun and gradually carried on in me, even from my childhood.

I was born in the month called July, 1624, at Drayton-in-the-Clay, in Leicestershire. My father's name was Christopher Fox; he was by profession a weaver, an honest man, and there was a Seed of God in him. The neighbors called him "Righteous Christer." My mother was an upright woman; her maiden name was Mary Lago, of the family of the Lagos, and of the stock of the martyrs.

In my very young years I had a gravity and steadiness of mind and spirit not usual in children, insomuch that when I saw old men behave lightly and frivolously toward each other, I had a dislike raised in my heart, and said within myself, "If ever I come to be a man, surely I shall not do so, nor be so foolish."

When I came to eleven years of age I knew pureness and righteousness; for while a child I was taught how to walk to be kept pure. The Lord taught me to be faithful in all things, and to act faithfully two ways: inwardly to God, and outwardly to man, and to keep to "Yes" and "No" in all things. For the Lord showed me that though the people of the world have mouths full of deceit and changeable words, yet I was to keep to "Yes" and "No" in all things, and that "my words should be few and savoury, seasoned with grace" (Colossians 4:6), and that I might not eat and drink to make myself indulgent, but for health, using the creatures in their service, as servants in their places, to the glory of Him that created them.

As I grew up, my relations thought to have made me a priest, but others persuaded to the contrary. So I was put to a man who was a shoemaker by trade and dealt in wool. He also used grazing and sold cattle, and a great deal went through my hands. While I was with him he was blessed, but after I left him he went bankrupt and came to nothing. I never wronged man or woman in all that time, for the Lord's power was with me and over me to preserve me.

While I was in that service I used in my dealings the word "Verily," and it was a common saying among those that knew me, "If George says 'Verily,' there is no altering him." When boys and rude persons would laugh at me, I let them alone and went my way; but people had generally a love to me for my innocence and honesty.

When I came towards nineteen years of age, being upon business at a fair, one of my cousins whose name was Bradford, having another professor with him, came and asked me to drink part of a jug of beer with them. I, being thirsty, went in with them, for I loved any who had a sense of good or that sought after the Lord. When we had drunk a glass apiece, they began to drink healths and called for more drink, agreeing together that he that would not drink should pay all. I was grieved that any who made profession of religion should offer to do so. They grieved me very much, having never had such a thing put to me before by any sort of people.

Therefore I rose up, and, putting my hand in my pocket, took out a groat and laid it upon the table before them, saying, "If it be so, I will leave you." So I went away; and when I had done my business I returned home, but did not go to bed that night, nor could I sleep, but sometimes walked up and down and sometimes prayed and cried to the Lord, who said to me: "You see how young people go together into vanity, and old people into the earth; you must forsake all, young and old, keep out of all, and be as a stranger to all."

Then, at the command of God, the ninth of the Seventh month, 1643, I left my relations and broke off all familiarity or fellowship with young or old. I passed to Lutterworth, where I stayed some time. From there I went to Northampton, where also I made some stay; then passed to Newport Pagnell, from which, after I had stayed awhile, I went to Barnet in the Fourth month, called June, in the year 1644.

As I thus traveled through the country, professors took notice of me and sought to be acquainted with me; but I was afraid of them, for I was sensible they did not possess what they professed.

During the time I was at Barnet a strong temptation to despair came upon me. I then saw how Christ was tempted, and mighty troubles I was in. Sometimes I kept myself retired to my chamber, and often walked solitary in the Chase to wait upon the Lord. I wondered why these things should come to me. I looked upon myself and said, "Was I ever so before?" Then I thought, because I had forsaken my relations I had done wrong against them.

So I was brought to call to mind all my time that I had spent, and to consider whether I had wronged any. But temptations grew more and more, and I was tempted almost to despair; and when Satan could not effect his design upon me that way, he laid snares and baits to draw me to commit some sin, by which he might take advantage to bring me to despair.

I was about twenty years of age when these exercises came upon me; and some years I continued in that condition, in great trouble; and I wished I could have put it from me. I went to many a priest to look for comfort, but found no comfort from them.

From Barnet I went to London, where I took a lodging and was under great misery and trouble there; for I looked upon the great professors of the city of London, and saw all was dark and under the chain of darkness. I had an uncle there, one Pickering, a Baptist; the Baptists were tender then; yet I could not share my mind with him, nor join with them, for I saw all, young and old, where they were. Some tender people would have had me stay, but I was fearful, and returned homeward into Leicestershire, having a regard upon my mind to my parents and relations, lest I should grieve them, for I understood they were troubled at my absence.

Being returned into Leicestershire, my relations would have had me married; but I told them I was but a lad, and must get wisdom. Others would have had me join the auxiliary band among the soldiery, but I refused, and was grieved that they offered such things to me, being a tender youth.

Then I went to Coventry, where I took a chamber for awhile at a professor's house, till people began to be acquainted with me, for there were many tender people in that town. After some time I went into my own country again, and continued about a year in great sorrow and trouble, and walked many nights by myself.

Then the priest of Drayton, the town of my birth, whose name was Nathaniel Stephens, came often to me, and I went often to him; and another priest sometimes came with him; and they would give place to me to hear me, and I would ask them questions and reason with them. This priest Stephens asked me why Christ cried out upon the cross, "My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?" (Matthew 27:46), and why He said, "If it be possible, let this cup pass from me: nevertheless not my will, but thine, be done" (Matthew 26:39; Luke 22:42)?

I told him that at that time the sins of all mankind were upon Him, and their iniquities and transgressions with which He was wounded (Isaiah 53:5), which He was to bear and to be an offering for as He was man; but He died not as He was God. So, in that He died for all men, "tasting death for every man" (Hebrews 2:9), He was an offering for the sins of the whole world (1 John 2:2). This I spoke, being at that time in a measure sensible of Christ's sufferings. The priest said it was a very good, full answer, and such a one as he had not heard. At that time he would applaud and speak highly of me to others; and what I said in discourse to him on weekdays, he would preach of on First-days, which gave me a dislike of him. This priest afterwards became my great persecutor.

After this I went to another ancient priest at Mancetter, in Warwickshire, and reasoned with him about the ground of despair and temptations. But he was ignorant of my condition; he told me to take tobacco and sing psalms. Tobacco was a thing I did not love, and psalms I was not in a state to sing; I could not sing. He told me to come again and he would tell me many things; but when I came he was angry and peevish, for my former words had displeased him. He told my troubles, sorrows, and griefs to his servants, so that it got out among the milk-lasses. It grieved me that I should have opened my mind to such a one. I saw they were all miserable comforters (Job 16:2), and this increased my troubles upon me.

I heard of a priest living about Tamworth who was accounted an experienced man. I went seven miles to him, but found him like an empty, hollow cask.

I heard also of one called Dr. Cradock of Coventry, and went to him. I asked him the ground of temptations and despair, and how troubles came to be wrought in man. He asked me, "Who were Christ's father and mother?" I told him Mary was His mother, and that He was supposed to be the son of Joseph, but He was the Son of God (Luke 3:23). Now, as we were walking together in his garden, the alley being narrow, I chanced, in turning, to set my foot on the side of a bed, at which the man was in a rage, as if his house had been on fire. Thus all our discourse was lost, and I went away in sorrow, worse than I was when I came. I thought them miserable comforters, and saw they were all as nothing to me, for they could not reach my condition.

After this I went to another, one Macham, a priest in high account. He would needs give me some medicine, and I was to have been let blood; but they could not get one drop of blood from me, either in arms or head (though they endeavored to do so), my body being as it were dried up with sorrows, grief, and troubles, which were so great upon me that I could have wished I had never been born, or that I had been born blind that I might never have seen wickedness or vanity, and deaf that I might never have heard vain and wicked words, or the Lord's name blasphemed.

When the time called Christmas came, while others were feasting and amusing themselves, I looked out poor widows from house to house and gave them some money. When I was invited to marriages (as I sometimes was), I went to none at all; but the next day, or soon after, I would go and visit them, and if they were poor I gave them some money; for I had the means both to keep myself from being chargeable to others and to provide something to the necessities of those who were in need.

About the beginning of the year 1646, as I was going to Coventry and approaching towards the gate, a consideration arose in me: how it was said that "all Christians are believers, both Protestants and Papists." And the Lord opened to me that if all were believers, then they were all "born of God, and passed from death to life" (John 5:24; 1 John 3:14); and that none were true believers but such; and though others said they were believers, yet they were not.

At another time, as I was walking in a field on a First-day morning, the Lord opened to me that being bred at Oxford or Cambridge was not enough to fit and qualify men to be ministers of Christ; and I wondered at it, because it was the common belief of people. But I saw it clearly as the Lord opened it to me, and was satisfied, and admired the goodness of the Lord, who had opened this thing to me that morning. This struck at priest Stephens's ministry, namely, that "to be bred at Oxford or Cambridge was not enough to make a man fit to be a minister of Christ." So that which opened in me I saw struck at the priest's ministry.

But my relations were much troubled that I would not go with them to hear the priest; for I would go into the orchard or the fields, with my Bible, by myself. I asked them, "Did not the Apostle say to believers that they needed no man to teach them, but as the anointing teacheth them?" (1 John 2:27). Though they knew this was Scripture, and that it was true, yet they were grieved because I could not be subject in this matter—to go hear the priest with them.

I saw that to be a true believer was another thing than they looked upon it to be; and I saw that being bred at Oxford or Cambridge did not qualify or fit a man to be a minister of Christ. What then should I follow such for? So neither them, nor any of the dissenting people, could I join with; but I was as a stranger to all, relying wholly upon the Lord Jesus Christ.

At another time it was opened in me that God, who made the world, "did not dwell in temples made with hands" (Acts 7:48; 17:24). This at first seemed a strange word, because both priests and people used to call their temples, or churches, dreadful places, holy ground, and the temples of God. But the Lord showed me clearly that He did not dwell in these temples which men had commanded and set up, but in people's hearts; for both Stephen and the apostle Paul bore testimony that He did not dwell in temples made with hands (Acts 7:48; 17:24), not even in that which He had once commanded to be built, since He put an end to it; but that His people were His temple, and He dwelt in them (1 Corinthians 3:16; 6:19). This opened in me as I walked in the fields to my relations' house.